MANILA, Nov (IPS) – The recent collapse of the global economy, caused by among other things the lack of regulation of financial markets, has further eroded the credibility of neoliberalism. And yet it continues to exercise a strong influence on the majority of economists and economic managers, for whom, despite its obvious shortcomings, it remains the default discourse.

MANILA, Nov (IPS) – The recent collapse of the global economy, caused by among other things the lack of regulation of financial markets, has further eroded the credibility of neoliberalism. And yet it continues to exercise a strong influence on the majority of economists and economic managers, for whom, despite its obvious shortcomings, it remains the default discourse.

Why the continuing invocation of neoliberal mantras when the promises of this doctrinaire approach have been contradicted at almost every turn by reality?

Neoliberalism is a perspective that champions the market as the prime regulator of economic activity and seeks to limit the intervention of the state in economic life to a minimum.

In recent times neoliberalism has become identified with economics, given its hegemony as a paradigm within the discipline, that is, its exclusion of other perspectives as legitimate ways of doing economics.

Since economics is regarded in many quarters as a hard science, much like physics -being, for instance, the only social science for which there is a Nobel Prize- neoliberalism has had a tremendous and pervasive influence not only in academic circles but in policy circles as well. While the University of Chicago, home to neoliberal economic guru Milton Friedman, became the font of academic wisdom, in technocratic circles the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank were seen as the key institutions that translated this theory into policy with a set of practical prescriptions that were applicable to all economies.

It is surprising to realise how recently neoliberalism became a hegemonic paradigm. As late as the mid-1970s Keynesian economics, which promoted a good dose of state intervention as necessary for stability and steady growth, was the orthodoxy. In what used to be known as the Third World, developmentalism, which prescribed Keynesian economics to economies that were still insufficiently penetrated and transformed by capitalism, was the dominant approach. There was a conservative brand of developmentalism and a progressive one, but both saw the state, rather than the market, as the central mechanism of development.

I believe that are three reasons why neoliberalism, despite its failures, remains dominant.

First, in certain developing countries like the Philippines, corruption continues to be pervasive as an explanation for underdevelopment. Therefore, it is argued, because the state is the source of corruption, increasing the state’s role in the economy, even as a regulator, is viewed with scepticism. Neoliberal discourse ties in very neatly with this corruption theory, with its minimisation of the role of the state in economic life and its assumption that making market relations more dominant in economic transactions at the expense of the state will reduce the opportunities for corruption by both economic and state agents.

For instance, for many Filipinos, and not only in the middle class, it is the corrupt state -and not the relations of inequality spawned by the market and the erosion of national economic interests brought about by the liberalisation of trade and capital markets- that continues to be the main obstacle to the greater good. It is seen as the biggest impediment to development and sustained economic growth. Corruption, of course, must be condemned for moral and political reason, but this supposed correlation between corruption and underdevelopment and poverty has little basis in fact.

Second, despite the deep crisis of neoliberalism, no credible alternative paradigm or discourse has emerged, either locally or internationally. There is nothing like the challenge that Keynesian economics posed to market fundamentalism during the Great Depression in the early 1930s. The challenges posed by star economists like Paul Krugman, Joseph Stiglitz, and Dani Rodrik continue to be made within the confines of neoclassical economics, with its equation of social welfare with the reduction of the unit cost of production.

And third, neoliberal economics continues to project a ‘hard science’ image because of the fact that it has been thoroughly mathematised. In the aftermath of the recent financial crisis, this extreme formalisation and mathematisation of the discipline has come under criticism from within the economics profession itself, with some contending that methodology rather than substance has become the end of economic practice, and that as a result the discipline has lost its contact with real-world trends and problems. It is worthwhile to note that John Maynard Keynes, a mathematical mind himself, opposed the mathematisation of the discipline precisely because of false sense of solidity that it gave to economics. As his biographer Robert Skidelsky notes, Keynes was “famously sceptical about econometrics”; numbers for him were “simply clues, triggers for the imagination”, rather than the expressions of certainties or probabilities of past and future events.

Getting over neoliberalism, thus, will involve getting beyond the worship of numbers that often shroud the real and beyond the scientism that masks itself as science. (END/COPYRIGHT IPS)

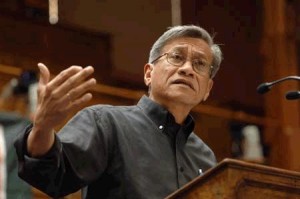

(*) Walden Bello, member of the House of Representatives of the Republic of the Philippines, is president of the Freedom from Debt Coalition and senior analyst at the Bangkok-based research and advocacy institute Focus on the Global South.